Is Trump's troop buildup in US cities a declaration of war — or something else?

LOS ANGELES — Over the weekend, President Donald Trump shared a doctored AI image of himself as Lt. Col. Bill Kilgore, the crazed cavalry commander in the 1979 Vietnam War film, "Apocalypse Now," crouched in a black Stetson hat in front of a flaming Chicago skyline abuzz with black helicopters. "'I love the smell of deportations in the morning,'" Trump wrote on Truth Social. "Chicago about to ...

California National Guard stand guard as protesters gather in front of the Edward R. Roybal Federal Building during the No Kings protests in Los Angeles on June 14, 2025.

Keith Birmingham/The Orange County Register/TNS

LOS ANGELES — Over the weekend, President Donald Trump shared a doctored AI image of himself as Lt. Col. Bill Kilgore, the crazed cavalry commander in the 1979 Vietnam War film, "Apocalypse Now," crouched in a black Stetson hat in front of a flaming Chicago skyline abuzz with black helicopters.

"'I love the smell of deportations in the morning,'" Trump wrote on Truth Social. "Chicago about to find out why it's called the Department of WAR."

Trump has long promised to deploy the National Guard to America's major urban hubs. But his unprecedented push this summer to deploy military convoys into Los Angeles and Washington, D.C. — and drumbeat of threats to send yet more into cities from Baltimore to San Francisco — has left many Americans divided on whether his administration is trying to protect people in Democratic-controlled cities or wage war on them.

When Trump first sent troops into L.A. in June, he argued federal immigration agents needed protection from locals who tried to obstruct them from fulfilling their mission. In August, he deployed the National Guard to Washington, D.C., seizing on instances of violent crime to claim a public emergency.

And now he has paired the issues of crime and immigration as he threatens Chicago, deploying militaristic imagery and rhetoric that break longstanding American norms.

As Trump goads Democratic-led cities, dubbing them poorly run "hellholes," Americans are grappling with a fundamental question of American democracy: Is Trump simply fulfilling his election mandate to ramp up deportations and combat crime, as he and his supporters argue, or ushering in a new era of American authoritarianism?

Trump's critics warn that he is exaggerating crime in American cities to score political points. In deploying troops to Los Angeles and D.C., they argue, Trump is setting up a military police state that targets political opponents, tramples on due process, installs loyalists over institutionalists, and erodes longstanding distinctions between the military and domestic law enforcement.

"This is how authoritarians behave, this is not how the leader of a free democracy behaves." said Elizabeth Goitein, senior director of the Liberty and National Security Program at the Brennan Center for Justice. "He is taking a page from authoritarian rulers around the world who have used crime as an excuse to consolidate power and suppress rights."

Conservatives tend to brush aside such concerns, arguing that Trump's deployment of troops simply delivers on a campaign promise. They note he ran on a platform of mass deportations and fighting crime in major cities.

"There's a problem to be dealt with there," said James E. Campbell, professor emeritus of political science at the University at Buffalo. "He has the constitutional authority to employ the National Guard, and that's part of the powers of commander in chief in Article II. What's peculiar here is some cities don't want the help — or at least the leaders of the cities."

While the courts will ultimately settle the legal questions of what Trump can do, he seems to be betting that he can put Democratic leaders in a defensive position at a time when polls show the vast majority of Americans are worried about crime.

When Illinois' Democratic Gov. J.B. Pritzker pushed back this weekend against Trump's Chicago plans, accusing the president of "threatening to go to war with an American city," Trump insisted he was not spoiling for a fight.

"We're not going to war," Trump told reporters at the White House. "We're going to clean up our cities."

Democrats say Trump is scaremongering about crime in American cities to score points against his political enemies, noting that homicides and other violent crimes have dropped over the last five years in cities across the nation.

According to a recent analysis by the Council on Criminal Justice, a policy think tank, violent crime is lower in most cities than the pandemic peak of 2020-21. But the report noted that most of the decline in the national homicide rate has been driven by large drops in cities with high homicide rates, such as Baltimore and St Louis. More than half of sample cities continue to experience homicide levels above pre-2020 rates.

For many Americans, crime remains a potent political issue.

About 81% of Americans and 68% of Democrats, according to a recent survey from the Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research, see crime as a "major problem" in large cities.

But it remains to be seen if Americans will warm to Trump's hard-line tactics: about 55% of Americans in the AP poll said it's acceptable for the U.S. military and National Guard to assist local police in big cities, but less than a third support federal troops taking control of city police departments.

::

Throughout the 2024 election, Trump threatened to deploy the National Guard to fight crime.

"In cities where there has been a complete breakdown of law and order, where the fundamental rights of our citizens are being intolerably violated," he promised in his Agenda47 campaign platform. "I will not hesitate to send in federal assets including the National Guard until safety is restored."

Still, there was some shock when Trump deployed the National Guard and U.S. Marines to L.A. in June after a clash erupted in the heavily Latino city of Paramount as immigration agents ratcheted up his deportation agenda.

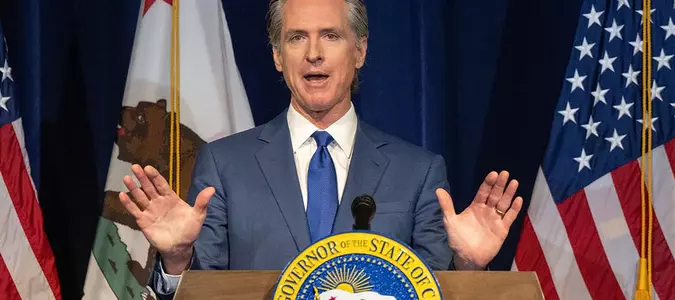

The conflict fell short of an all-out collapse of law and order. After Border Patrol agents were spotted setting up a staging area outside a Home Depot, hundreds of protesters gathered, some hurled rocks at federal vehicles as agents fired tear gas and flash-bang grenades at the crowd. Within hours, Trump ordered 2,000 National Guard soldiers to L.A.— against the will of California Gov. Gavin Newsom — to protect federal agents and property.

Sending in the National Guard without a governor's consent was a highly unusual step. The last time it happened was in 1965, when Lyndon B. Johnson federalized the Alabama National Guard to protect civil rights marchers marching from Selma to Montgomery.

But L.A. was not a one-off for Trump. In August, Trump announced he would take federal control of Washington, D.C.'s police department and activate National Guard troops to help "reestablish law and order." The city, he said, had been "overtaken by violent gangs and bloodthirsty criminals, roving mobs of wild youth, drugged-out maniacs and homeless people."

Dist. Atty. Brian Schwalb, the elected attorney general of the District of Columbia, argued "there is no crime emergency" in D.C. "Violent crime in DC reached historic 30-year lows last year," Schwalb noted, "and is down another 26% so far this year."

But Trump put Democrats on the defensive as he seized on a handful of violent cases in the nation's capital: two Israeli embassy staffers fatally gunned down in May, a congressional intern shot dead in June and an administration staffer assaulted in an attempted carjacking in August.

And he has adopted a similar strategy as he threatens to send troops to Chicago, highlighting a violent Labor Day weekend, in which nine people were killed and more than 50 injured across the city.

Chicago has long struggled with violent crime, but city officials note that homicides and shootings have declined, putting the city on track for its lowest homicide rate in half a century.

Mayor Brandon Johnson said homicides are down 30% in the last year in Chicago and his police department has taken 24,000 guns off the street, most of which came from Republican-led states, since he took office in May 2023.

"This stunt that this president is attempting to execute is not real. It doesn't help drive us towards a more safe, affordable, big city," Johnson said last month as he called on Trump to release $800 million in violence prevention funds that the federal government cut in April.

Already, Trump has declared implausibly quick results in curbing crime in Washington, D.C..

"D.C. was a hellhole and now it's safe," the president declared less than two weeks after deploying troops to the nation's capital. "Within one week, we will have no crime in Chicago."

When asked about Trump's strategy, Adam Gelb, the president and chief executive of the Council on Criminal Justice, said the obvious challenge was the Trump administration's solutions tended to be, "by definition, short term dopamine hits and not sustainable long term solutions."

"That's what history tells us: we can have short-term impact with shocks to the system like this, but they tend to be fleeting."

Asked what would happen if the shock to the system was permanent, Gelb said he did not know.

"It hasn't been tested," Gelb said, "not in this country with respect to deployment of troops in massive numbers."

Ultimately, Gelb said, Trump's incursion into cities was "testing Americans' tolerance for crime and militarization."

"If there's a perception that these tactics are responsible for dramatic reductions in crime," he asked, "will people become more tolerant of them?"

::

Trump has suggested that Americans will allow him unlimited powers if he is perceived as stopping crime.

"Most people are saying, 'If you call him a dictator, if he stops crime, he can be whatever he wants,' " Trump said last month in a televised Cabinet meeting. "I am not a dictator, by the way,"

"I'm the president of the United States," he added. "If I think our country is in danger — and it is in danger in these cities — I can do it."

Daniel Treisman, a professor of political science at UCLA, said Trump is "the most extreme case yet of a leader who comes to power in a long-established democracy and wants to act like an authoritarian — to break down all restrictions on his power and intimidate his enemies."

Most alarming of all, he said, was the Trump administration's purging of professionals from federal agencies such as the Department of Justice and Federal Bureau of Investigation in favor of loyalists.

The co-author of "Spin Dictators: The Changing Face of Tyranny in the 21st century," Treisman said Trump's aims appeared to closely resemble those of Viktor Orbán, prime minister of Hungary, or Nayib Bukele, president of El Salvador.

"I would like to believe that he will face a lot more obstacles than those leaders did," Treisman said.

Even if a majority of Americans think Trump is right that crime is a problem — or a substantial number support indefinite occupations of American cities or the elimination of due process — some argue that doesn't make it democratic.

"There's no such thing as electing a president to undo democracy and violate the rule of law," Goitein said. "He can't say, 'Well, the American people elected me to shred the Constitution.' "